A group of Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) in Kampala has urged the government to increase funding to the malaria control programme.

The CSOs say the Malaria Control Program being implemented as part of the Global Fund initiative, has not received sufficient funds from government as outlined in the Uganda Malaria Reduction Strategic Plan, making the objectives of the plan unrealistic.

Records, according to CSOs, show that over 16 million malaria cases were reported at Uganda’s health facilities in 2013 alone, forcing government to launch the Uganda Malaria Reduction Strategy 2014-2020 with specific objectives to fight the malaria pandemic to the lowest levels possible.

Clinically diagnosed malaria is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Uganda, accounting for 30-50 percent of outpatient visits at health facilities, 15-20 percent of all hospital admissions, and up to 20 percent of all hospital deaths. 27.2 percent of inpatient deaths among children under five years of age are due to malaria.

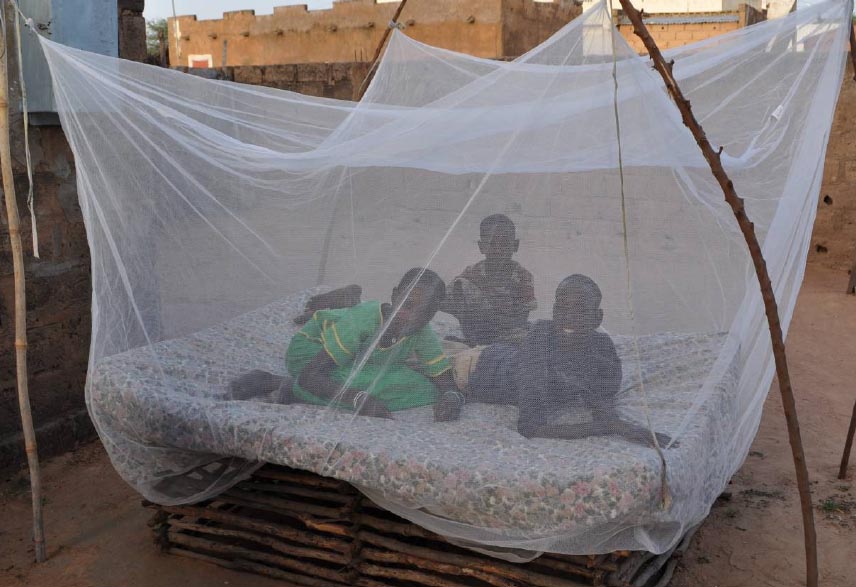

Among the objectives to prop the programme, the government intended by the year 2017 to achieve and sustain protection of at least 85 percent of the population through malaria prevention measures, among them the on-going distribution of the insecticide-treated nets (ITNs).

Under the programme, by the year 2018, government also wants to achieve and sustain at least 90 percent of malaria cases in the public and private sectors and community level, with patients receiving prompt treatment according to national guidelines.

However, with the slow pace government is implementing the strategic plan, and the little money it is allocating to the programme, CSOs say not much will be achieved.

To achieve the above targets the strategic plan requires a total funding estimated at US$1.361 billion over the six year period, implying that Uganda needed to invest US$ 226.6 million (Shs793.9 billion) per year, which the CSOs say is almost the entire budget for the Ministry of Health.

The CSOs say the direct costs of malaria in Uganda include a combination of personal and public expenditures on both prevention and treatment of the disease. Personal expenditures, they say, include individual or family spending on ITNs, doctors’ fees, antimalarial drugs, transport to health facilities, and support for the patient and sometimes an accompanying family member during hospital stays.

Public expenditures include spending by government on maintaining health facilities and health care infrastructure, publicly managed vector control, education and research.

The CSOs say that a significant percentage of deaths occur at home and are not reported by any system. According to official reports, Uganda’s high rates of malaria affect young children and pregnant women in rural areas who experience extreme poverty, limited access to healthcare services, and lack of education.

A recent study shows that Uganda spends almost Shs1,200 billion on diagnosing and treating malaria annually, or about Sh40,000 per person. This includes the money spent by the Government, donors, NGOs and private patients.

The Government alone spends sh63 billion per year on fighting malaria, 10 percent of the total health budget.

“Malaria is a preventable disease associated with slow socio-economic development and poverty. The determinants of malaria have roots beyond the health sector and the roles of other sectors need to be harnessed to prevent and control malaria in this country,” the CSOs urge government.

They say that malaria prevention and control programs need to have a multi-sectorial dimension. “The slow pace in reducing the malaria burden in Uganda and the renewed international call for a multi-sectorial action necessitates reforms in Uganda’s efforts to reduce malaria,’ the agitate.

According to Word health Organization , annual economic growth in countries with high malaria transmission has historically been lower than in countries without malaria. Economists believe that malaria is responsible for a growth penalty of up to 1.3 percent per year in some African countries.

According to Ministry of Health, maleria is a major public health problem associated with slow socio-economic development and poverty and the most frequently reported disease at both public and private health facilities in Uganda.

“Malaria has negative health and economic effects, and restricts the productivity of our population. Increased ITN coverage and education, improved access to and delivery of treatment, and emergency control of malaria are essential to control malaria in Uganda,” health officials recommend.