A coalition of 174 civil society organisations has called on international donors, including the UK government, to drop support for the Bridge International Academies (BIA), a private school company operating in Africa including Uganda.

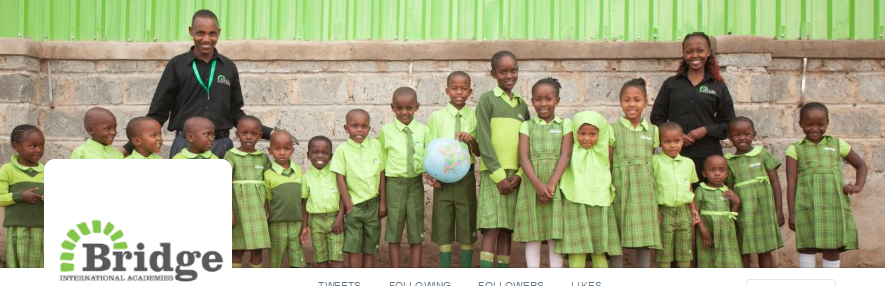

BIA provides technology-driven education in more than 500 primary and nursery schools in Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria, Liberia and India, and Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg are among the high-profile philanthropists from whom the American startup has received funding.

But late last year Uganda’s high court ordered the closure of 63 Bridge schools last year, ruling that they provided unsanitary learning conditions, used unqualified teachers and were not properly licensed. No schools have been closed and Bridge is in dialogue with a government team, that includes among other stakeholders the Minister of Education Janet Museveni, who has previously expressed skeptism about the operations of Bridge schools in Uganda.

And in a statement, ‘anti-Bridge’ campaign groups said the firm charges prohibitively high fees and that teachers are poorly paid, receive little training, and are given inflexible, scripted lessons to read from tablets. The organisations also accused BIA of intimidating its critics, a claim the company has denied.

The statement, signed by organisations from 50 different countries including Global Justice Now and Amnesty International, cited research suggesting that the poorest students cannot afford to attend Bridge schools.

“BIA’s model is neither effective for the poorest children nor sustainable against the educational challenges found in developing countries,” said the campaigners, who alluded to “mounting institutional and independent evidence that raises serious concerns about BIA” and warned of “significant legal and ethical risks associated with investments” in the company.

In Kenya, sending three children to a Bridge school is estimated to represent almost a third of the monthly income of families living on $1.25 (94p) a day, according to a joint study by Kenya National Union of Teachers and Education International, a federation representing 32 million teachers and support staff. The researchers noted that teachers are required to work between 59 and 65 hours a week for a monthly salary of $100.

In April, following an inquiry into UK aid spending on education, the chairman of the UK parliament’s international development committee questioned whether grant funding should have been provided to Bridge.

“The evidence received during this inquiry raises serious questions about Bridge’s relationships with governments, transparency and sustainability,” Stephen Twigg wrote in a letter to the international development secretary, Priti Patel.

But Bridge’s model, under which teachers are given electronic tablets containing lesson plans, is seen by some as an answer to improving access to education in low-income countries.

And responding to the criticism from civil society groups, BIA said it provides high-quality education to marginalised and remote communities across Africa. The company pointed out that it costs an average of just under $7 (£5) a month to send a child to Bridge, and that 10% of students are on scholarships. BIA added that teachers work about 54 hours a week and are given high-quality training before and during their careers, with salaries – between $95 and $116 a month in Kenya – higher than in other non-formal schools.

“Our pupils are outperforming their peers in national exams over consecutive years. Our model means that we’re able to attract new investment towards solving one of the world’s most pressing problems: hundreds of millions of children who are not learning,” the Bridge statement said.

“Public schools and Bridge schools can and do operate side by side to serve communities in countries where there are major shortages of nurseries and primary schools. We help governments quickly address the gap between how many schools they have and how many they need.”

The UK Department for International Development said: “We have supported over 11 million children in primary and lower-secondary education from 2011-15, including over 5.3 million girls.

“Many of the world’s poorest countries rely on privately run schools to provide an education where state provision is failing. Without privately-run schools, millions of children would be denied an education.”