Tony Blair was not trying to “save” Colonel Gaddafi when he spoke to the dictator at the height of the Libyan conflict in 2011, he has told MPs.

The former prime minister confirmed he had “two or three” phone conversations within 24 hours with Gaddafi, having cleared it with David Cameron.

His aim was to get the dictator out of Libya “so that a peaceful transition could take place”.

But he conceded that the Gaddafi regime was “not sustainable”.

He defended his decision as prime minister to bring Gaddafi “in from the cold”, saying it may have prevented so-called Islamic State getting chemical weapons.

As part of the process, Gaddafi renounced weapons of mass destruction, bringing to a halt programmes to develop nuclear and chemical arms.

During his 90-minute appearance before the Commons foreign affairs committee, Mr Blair also said:

- Mr Cameron’s decision to intervene in Libya in 2011 was “well-intentioned” and done in “good faith”

- The line between intervention on humanitarian grounds and regime change is “pretty thin”

- Political evolution is always preferable to revolution because of the “chaos” and instability that tend to follow

- He had philosophical discussions with Gaddafi about the “third way,” among other issues, but the dictator’s views on the Middle East peace process were “eccentric”

- He told Downing Street in 2011 that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad had to go and it must happen quickly

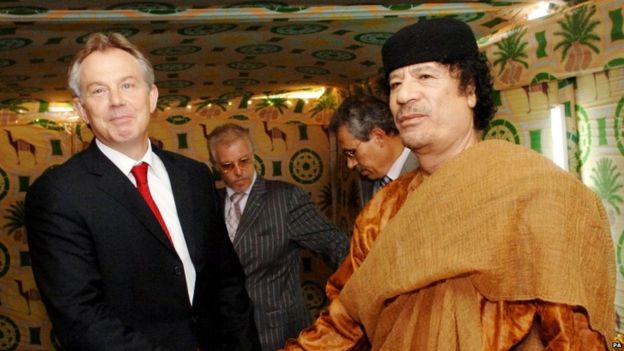

While in office, the ex-prime minister supported the West’s rapprochement with the regime of Colonel Gaddafi and even visited him in Libya in 2004.

Libya renounced its nuclear weapons programme as part of an international agreement but the West’s more accommodating relationship with the regime, which led to a number of commercial deals, came in for criticism after Gaddafi violently repressed a uprising during the so-called Arab Spring.

‘Huge prize’

Mr Blair said the decision to engage with Gaddafi, who was accused of sponsoring terrorism in the 1980s, had been difficult but he suggested there was a “huge prize” on offer from trying to normalise relations, in terms of security co-operation, and other issues were “not left to one side”.

“When I went to see him, Lockerbie, Yvonne Fletcher, were absolutely in my mind and part of the conversation,” he said.

“But I felt ultimately the game was worth it and I do believe it was worth it but is not to say I approve of what he did before or how he ran his country.”

Phone calls

As Libya descended into civil war in early 2011, Mr Blair said he decided to “use his relationship” with Gaddafi to try and persuade him to leave the country but quickly realised he had “no appetite” to do so.

“It has been presented as I was trying to save Gaddafi. I wasn’t trying to save Gaddafi. I was trying to get him to go.”

Asked who initiated the conversation, Mr Blair said he approached the Libyan leader off his own back, having first spoken to Downing Street and the US State Department.

“They (the calls) were all basically saying ‘there is going to be action unless you come up with an agreed process of change, If you don’t do that, they are going to come and get you out’.”

In light of Gaddafi’s subsequent killing, Mr Blair was asked if the UK, France and the US had exceeded the auspices of their United Nations mandate which authorised action to protect Libyan civilians from the risk of a potential massacre in Benghazi.

Mr Blair said he was not willing to criticise David Cameron for acting in the way he did, adding: “Once you engage in a military action to protect people against a regime, the line between that and (regime change) becomes pretty thin at a certain point.”

Instability

Although Parliament backed the UK’s action at the time, MPs are more critical of the intervention now, saying little thought was given to post-conflict planning, to reconciling warring factions and building inclusive institutions after the collapse of the Gaddafi regime.

Libya has been beset by instability since 2011. Since 2014 the country has had two rival parliaments – an Islamist-backed one in Tripoli and an internationally recognised government in the east of the country – amid UN attempts to broker a single government of national unity.

While the current chaos in Libya was a threat to the UK’s national security, Mr Blair said the international community was not wholly to blame, given that post-conflict stabilisation is always “very very tough” and Libya had been deliberately destabilised by radical Islamist groups.

Following Mr Blair’s appearance, the SNP said it would be seeking more “transparency” about the nature of his conversations with Gaddafi.

“The lessons of Libya, like Iraq, is that you cannot just bomb somewhere and move on,” said SNP MP Stephen Gethins.

Conservative ministers have defended the Libya intervention, former foreign secretary William Hague recently telling MPs that he would back similar action again while acknowledging that Libya had not turned out as the government had hoped.

Ministers have pointed to closer co-operation with the Libyan authorities on matters of mutual interest in recent years. Earlier this year, a Libyan man was arrested on suspicion of conspiracy to murder PC Yvonne Fletcher outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984.