Uganda’s debt has risen significantly, reflecting a renewed investment push financed through increased commercial borrowing, including from domestic borrowing, a new IMF report shows.

The report which does not mention the current debt says Uganda, like neighbouring Kenya, has not reached the debt burden indicators that show elevated risk, which means that Uganda can still borrow to finance projects.

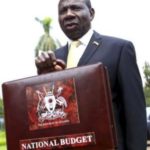

But Government says borrowing will not exceed 41.7 percent nominal debt to GDP, and according to the Budget Speech for the 2017/18 financial year read by the finance Minister Matia Kasaija, the country’s external and domestic debt has shot up to Shs28 trillion, equivalent to 33.8 per cent of the country’s GDP. The danger level of borrowing is 50 per cent of GDP.

However, according to the report that looks at economic developments and prospects among the world’s low-income countries, borrowing should be for productive projects.

On the other hand, the report says government debt in some of the world’s poorest countries is rising to risky levels. The report also focuses on the shift in the composition of creditors such as BRICS. It urges official creditors led by the World Bank and IMF to work together to find ways to ensure efficient coordination in the event of future debt restructurings for poor countries.

Analysis of the report shows that the drivers of the debt rise vary across countries. They include; shocks such as the sharp drop in commodity prices of 2014, which hit budget revenues in commodity exporters like Uganda, and natural disasters including the Ebola epidemic in West Africa.

Also civil conflict in counties like Somalia, Burundi, as well as high levels of public spending that were not linked to financing productive public investment, are part of the drivers. “Ample global liquidity played an important role in allowing for the rise of debt in low-income countries, by making it easier to borrow,” the report says.

Government debt is rising

“Budget deficits have been rising in most low-income countries during this decade where 70 per cent of low-income countries had higher government deficits in 2017 than during 2010-14. For commodity exporters, falling revenues contributed to higher deficits, whereas higher spending was the more important factor in other countries,” the report says.

The report says the current build-up of public debt comes in the wake of the low debt levels and robust growth that followed the international community’s actions to write off most of the debt of highly indebted poor countries—the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative , which left countries with more resources to spend on investment and education.

“Higher public deficits and debt levels are not necessarily undesirable. When countries borrow to pay for infrastructure investment, that can boost long-term growth, which in turn generates revenues to service the higher debt,” it says.

Threat of debt crises is soaring

Despite the rise in debt, the report says more than half of low-income countries are still at low or ‘moderate’ risk of defaulting on their debt service obligations. “However, the share of countries at elevated risk of debt distress, for example, Ghana, Lao P.D.R., and Mauritania, … already unable to service their debt fully has almost doubled to 40 per cent since 2013,” it says.

The IMF anticipates some stabilization of the debt build-up in the coming years but says the forecast is predicated in part on countries undertaking fiscal adjustment and carrying out ambitious economic reform programs to deliver stronger economic performance. “It will be very important that countries implement these reforms—otherwise the debt build-up is likely to continue,” the report says.

Borrowers have moved away from traditional official creditors such as multilateral institutions and members of the Paris Club towards non-Paris Club official bilateral creditors, sovereign bond issues, other foreign commercial lenders, and domestic sources, mainly banks, the report says.

But the new forms of private credit often come at shorter maturities and higher interest rates, yielding larger debt service burdens for the borrower countries and higher rollover risks when these debts mature, the report says. It adds: “These creditors, unlike the Paris Club members, do not have ready mechanisms for coordination with other creditors, which is likely to make any needed debt resolution more difficult.”

Several countries like Chad, Mozambique and the Republic of Congo have already fallen into debt distress, with some seeking to restructure their debt.

To help contain debt vulnerabilities in low-income countries, borrower countries, lenders, and the international institutions should all work together, the report says.