Africa is viewed by many as a continent that has failed to progress at a rate that is commensurate with its resources, and all this thanks partly to leaders who seem to have their priorities inverted.

Over fifty years after most of its countries attained Independence, several current African leaders (with the probable exception of Botswana president Ian Khama) seem lost at sea on how to change the lives of their respective citizenry, with almost a billion Africans wallowing in poverty and living on less than a dollar a day.

Indeed, enumerating the failures of the post-Independence African leaders can easily turn into a lucrative career opportunity for political historians telling the African leadership crisis in its true perspective.

‘The Stone Age did not come to an end because stones had been finished on the face of earth; it came to an end because of the ever-changing innovations,’ a scholarly friend once told me, when I asked about his rating of the performance of African leaders over the last five decades.

Indeed, it is apparent that what most of our leaders, past and present, lack is the innovative mind to turnaround the continent’s fortunes through harnessing its resource purse; what with the billions of dollars that have been sunk into the bottomless abyss that is Africa through aid.

As a result of the mostly unforgivable failures, alternative political voices and schools of thought have sprung up in different countries, trying to cause change to the status quo, with claims of providing ‘better leadership’. Unfortunately, most of the opposition figures that have castigated sitting regimes in Africa have failed to take the mantle of state, in order to give the respective citizens an insight in their ‘better leadership’ claims.

In Uganda, the National Resistance Movement/Army (NRM/A), a political organization that has been in power for 30 years, has faced different shades of opposition since coming to power in 1986. First was the military opposition of defeated groups like the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA); the Holy Spirit Movement (HSM) of Alice Lakwena and the Lords Resistance Movement/Army (LRM/A) of Joseph Kony among many others. Then, at around the same time there was the political opposition mainly orchestrated by the old political parties among them the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC); a splinter group of both the Democratic Party (DP) and the Conservative Party led by led by Michael Kaggwa and maverick politician John Ken Lukyamuzi, respectively.

But as the NRM/A hold onto power gained tract, dissenting voices emerged from within the organisation’s ideologues and these included among others Eriya Kategeya, Augustine Ruzindana, Amanya Mushega, Miria Matembe, John Gregory Mugisha Muntu, David Sejusa and Dr Warren Kizza Besigye Kifefe. Of the NRM/A dissenters, Dr Besigye, a retired Colonel, has since put up the most spirited pursuit of the change in the political status quo in Uganda over the last 20 years. Since 1991 when he authored a dossier castigating the NRM/A government for allegedly deviating from the principles that led its ideologues to wage a five-year ‘liberation struggle’, Dr Besigye has increasingly given the state a restless time, with his actions leading him on a collision course with the authorities on several occasions.

Dr Besigye has contested against the NRM and its leader Yoweri Museveni for four times now, the first being in 2001, in which said he was cheated of victory, later petitioning the Supreme Court. In its ruling then, the SC noted that there were ‘irregularities’ but that they were ‘not substantial to alter the results of the elections’. Notably, in all the three subsequent elections Mr Besigye, running under the banner of the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), has contested against the same Museveni, with repeated claims of his victory being stolen through electoral malpractices including vote-rigging, intimidation and voter-bribery. Well, Besigye is yet to become president so that he practically shows us how differently he would carry on with affairs of state.

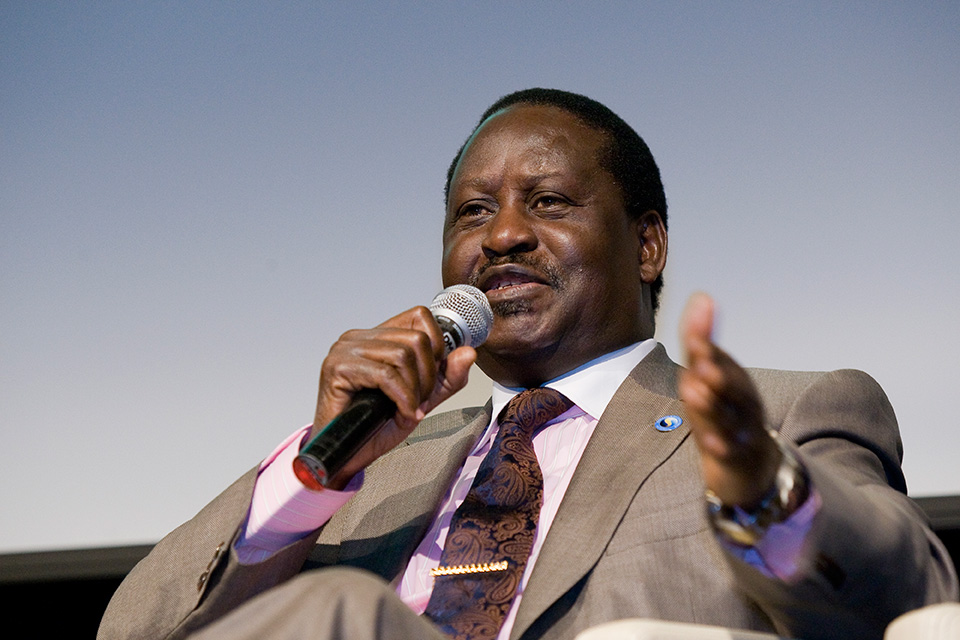

But Besigye is not alone in this thinking that he can change the course of political events in the respective Africa countries. In neighbouring Kenya Raila Amollo Odinga has over the years earned himself the tag ‘The best President Kenya never had’. Currently the leader of a political organization called the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), Raila Odinga, the son of Kenya’s founding Vice President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, has for the last four decades strived to ensure that the political history in Kenya changes. His foray into Kenyan politics began to take shape in 1982 when he was linked to a coup against Daniel Arap Moi. Since then, even when serving in government, he has severally run into trouble with the authorities, doing lengthy exile and jail time, the longest stint being over six years served at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison.

Odinga has contested for the Kenyan presidency thrice, the first in 1997 when he run under the banner of the National Development Party (NDP) against Arap Moi of the Kenay African Union (KANU); Democratic Party (DP)’s Emilio Mwai Kibaki and Michael Kijana of the FORD-Kenya. Ten years later, this time under the umbrella of the ODM Odinga contested against DP’s Mwai Kibaki and lost. He contested the results, a stand that saw Kenya descend into chaos in 2007/8, culminating in the death of over 1000 people. Consequently, Mr Odinga was to join a coalition government, serving as Executive Prime Minister under President Kibaki. The ‘convenient political alliance’ was prickly.

And, in 2013 Mr Odinga contested against current President Uhuru Kenyatta and lost but claimed he had been cheated of victory. He petitioned the Supreme Court but his petition was dismissed, sealing his place as the de facto Kenyan opposition leader up to 2017.

But since the failures in Africa seem to resonate from country to country, it is not surprising that there will always be rubble rousers spread across the continent, all claiming they want to offer ‘better leadership’.

In neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo, perennial contestant Etienne Tsishekedi Wa Mulumba has once again declared his interest in the DRC presidency, to run against incumbent Joseph Kabila and millionaire Moise Katumbi. A five-decade-serving politician and three-time Prime Minister under Dictator Joseph Desire Mobutu Sese Seko Ngbendu Wazabanga between 1991 and 1997, Mr Tsishekedi’s quest to become DRC president began in 2006 when he campaigned under the banner of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), challenging incumbent Joseph Kabila. He was, however, to withdraw from the elections, saying they had been rigged even before the voting took place. Mr Tshisekedi was to stand again in 2011, lose the election but declare himself the ‘elected president’ of DRC, sending the security forces in an overdrive that culminated in his being restricted at home (unofficial house arrest).

Then enter Morgan Richard Tsvangirai, a trade unionist-turned politician who made his first foray in politics in 1995. In 2002, Tsvangirai of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) challenged long-serving Zimbabwe President Robert Gabriel Mugabe for presidency and claimed he lost after Mr Mugabe stole the election.

Tsvangirai was to contest for elections again in the first round in 2008, garnered a ‘majority vote’ that was contested, setting the ground for a run-off, participation in which he snubbed, saying it was not going to be ‘free and fair’. However, under pressure of the international community, Mr Mugabe, the Zimbabwe leader since Independence in 1980 was to concede and name Tsvangirai Prime Minister in 2009, a position he held till 2013.

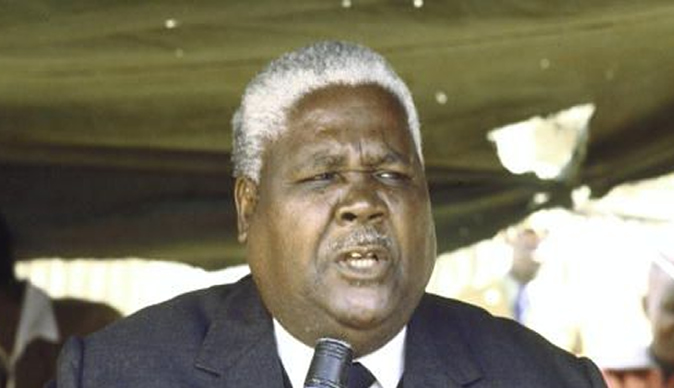

Earlier, the late Zimbabwean liberation war hero Joshua Nqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo, an on-and-off political colleague of then Prime Minister Mugabe, thrice rejected becoming a ceremonial president, a decision that catapulted the late Reverend Canaan Banana to the presidency. And in 1983, precisely three years after Independence Mr Nkomo was to flee to exile in the United Kingdom, from where he penned a 117-point missive to Mr Mugabe, detailing the ills of his government.

However, after a series of such political disagreements, in 1987 Nkomo’s party, the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU) merged with the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) of Mr Mugabe to form the ZANU-Patriotic Front, a temporary alliance of convenience that saw Mr Nkomo, fondly referred to as ‘Father Zimbabwe’, become Vice President for 12 years, from 1987 to 1999.

Meanwhile, as other opposition political activists were busy keeping their respective governments on their toes, Jonas Malheiro Savimbi, the leader of the National Union for the Total Liberation of Angola (UNITA), one of Angola’s liberation war factions waging war against the Portuguese, was also another restless soul in Angola, who felt that the Peoples Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA’s), Agostino Neto, the first president of independent Angola who served up to his death in 1979, was not doing enough to steer the country in the right direction.

And following Neto’s death, Savimbi was to turn his guns against his successor Jose Eduardo Dos Santos, fighting a lengthy guerilla war that claimed several tens of thousands of lives. Savimbi was taken out in a fierce battle with Angolan government troops in 2002, bringing to an end a ‘psuedo military-politico and opposition career’ that spanned over 30 years.

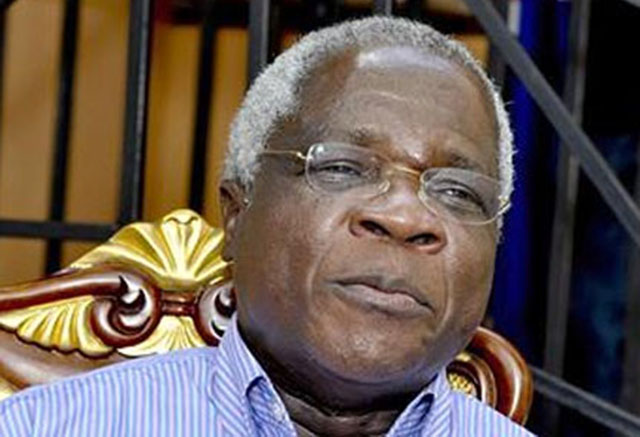

Then there is another Alfonso Dhlakama, the leader of the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO). Born in 1953, Dhlakama was involved in the pre-Independence liberation struggle in Mozambique and, after the country gained independence under the leadership of Samora Marcel’s Freeddom Liberation Movement (FRELIMO) in 1975, he continued fighting the government. And today, 41 years since Mozambique gained independence Dhlakama is still viciously opposed to the FRELIMO government of President Armando Guebuza.

Also, notable among the other opposition gurus that have straddled the African continent over the years is Laurent Desire Kabila, the father to current DRC president Joseph Kabila, who fought a guerilla war against the government of Mobutu Sese Seko. A pro-Lumumba supporter of long standing, dating back to the 1960s, Kabila toppled the long-serving dictator Mobutu in 1995 but was himself to be assassinated six years alter in 2001.

Then there is also chief Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, the Nigerian politician and military officer who led the war of secession of the Republic of Biafra for three years, from 1967 to 1970. He died in London in 2011 before realizing his ‘dream’ of an independent Biafra State.