A total of 817,883 candidates registered for the 2025 Primary Leaving Examination, according to the Uganda National Examinations Board. Of these, 807,313 candidates sat the examinations, while the rest were absent. A total of 730,233 candidates passed, while 77,080 were ungraded, meaning they failed to demonstrate the minimum competencies expected at the end of primary education.

In percentage terms, 90.4 percent of candidates passed, while 9.6 percent failed. Although the number of ungraded candidates declined from over 88,000 in 2024, the figure remains high for a system that has prioritised universal access, curriculum reform and expansion for more than two decades.

The distribution of results shows that 91,990 candidates attained Division One, 388,293 were placed in Division Two, 165,226 in Division Three, and 84,724 in Division Four. The pattern remains familiar. A relatively small group excels, the majority pass at middle levels, and a significant minority exits primary school without the expected competencies.

While releasing the results, UNEB Executive Director Dan Odongo acknowledged wide performance disparities across school types and regions. Learners from well-resourced urban schools continued to dominate the top grades, while government aided Universal Primary Education schools, particularly those in rural and hard to reach areas, accounted for a large share of candidates in the lower divisions and among the ungraded.

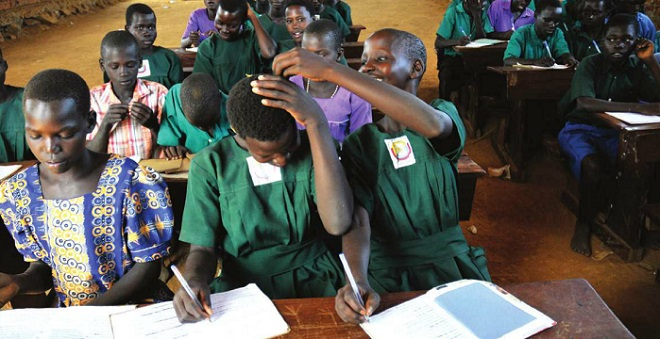

This reality points directly to the heart of the problem. Uganda operates a uniform national examination in a system where learning conditions are far from uniform. Pupils in village schools study in overcrowded classrooms, with limited learning materials and overstretched teachers, yet they are assessed using the same tools, timelines and standards as pupils in well facilitated urban schools.

There is no structured leniency, no contextual adjustment and no differentiated assessment to reflect the unequal environments in which children learn. In effect, the system measures everyone equally, even when opportunity is clearly unequal.

The results have also reopened debate over how success and failure at primary level are defined. Victoria University Vice Chancellor Dr. Lawrence Muganga has challenged the culture of treating national examinations for young learners as final judgments.

“The release of examination results is not news. It should be normal for every learner to sit an exam or undertake an assessment. Yet we become overly excited about a national exam for a 12 or 13 year old, while at the same time worrying that they might fail,” Muganga said.

Muganga questioned the logic of branding children as failures in a system that remains structurally unequal.

“Who declares a 13 year old a failure? Our education system is not yet as inclusive as we want it to be,” he said.

He pointed to Competency Based Education as a necessary shift away from memorisation and rigid timelines toward mastery and practical ability. Under this approach, competencies remain constant while time varies, allowing learners to progress when they are ready rather than when the calendar demands.

However, the 2025 PLE outcomes suggest that while policy direction has changed, implementation on the ground remains uneven, particularly in rural UPE schools where the conditions required to support competency based learning are still weak.

“It is no longer about what you can recall, but what you can do with what you know. A learner may score 60 percent and still be a problem solver. That is meaningful education,” Muganga said.

With over 730,000 candidates passing PLE, the primary education system is not in crisis. But with 77,080 pupils leaving primary school ungraded, the results expose a persistent structural gap between reform promises and classroom reality.

That gap explains why, year after year, tens of thousands of children reach the end of primary education without meeting national standards. Until reforms move beyond policy documents and reach the village classroom, the question posed by this year’s results will remain unavoidable.